The Quality Factor – Brix

In our last article, we determined that plants actually request attacks from pests and pathogens. Having established that, the next question becomes: How do we get plants to send the ‚good‘ signals and not the ‚bad‘ in a controlled environment? That’s where Brix comes in! (Didn’t read the article on ‚Plant Signals‘ yet? Click here)

Two indicators have a tremendous influence on the overall health of a plant, (internal) pH and Brix. Both can be measured relatively easily with some specialized instruments, but that’s not always practical. Fortunately, even without testing, there are specific techniques that will help your plants get healthier. We’ll focus on Brix in this article, and talk about pH in our next blog (which can be found here!).

The most common agricultural understanding of Brix measurement is the level of sugars within the plant tissue. The guy that created the Brix scale (Adolf Brix) defined it as the sugar content of an aqueous solution. This measure has been used for a long time to test the ripeness of fruits, like grapes and apples. The rule was; the higher the Brix, the riper (and more flavorful) the fruit, or the more ready for specific applications, like winemaking for example.

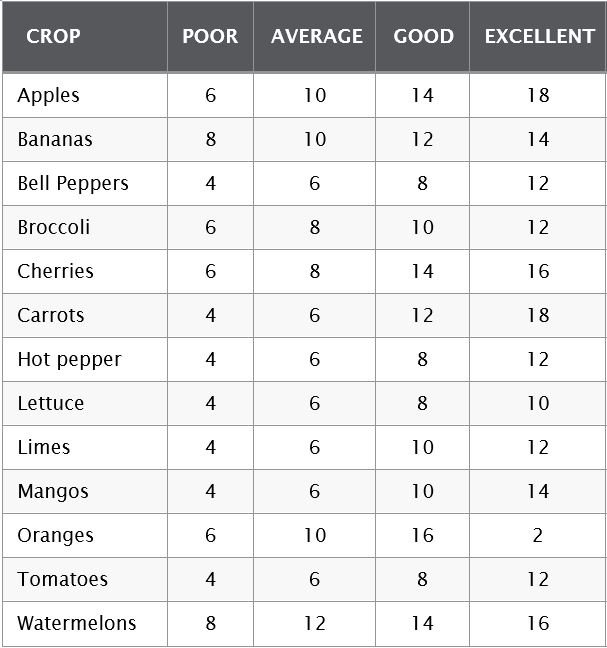

To give you an idea about good and bad Brix values, here’s a table with some common crops and indications of their quality according to Brix reading:

However, there’s not just sugar in plant tissue. There are tons of other compounds floating around in there like amino acids, vitamins, phytohormones, minerals, etc. All of these compounds have an effect on the Brix reading, which is why more and more researchers are expanding (or loosening) the Brix reading to be a reflection of the total dissolved solids in a solution. Even though Brix was originally designed to test only sugar levels, it is quickly becoming accepted as a key measure of overall quality and health.

Most important to understand about Brix is the effect on the plant. First, if there are more sugars and other beneficial components like minerals and amino acids (building blocks), the plant can build more quality compounds like oils, flavors, resins, etc. This makes the plant tastier and healthier for us. At the same time, decomposing insects and pathogens don’t like these compounds.

If you have a healthy plant reading a high Brix level, a spider mite, for example, will not be attracted by the plant. The high mineral content makes the plant repulsive to the mite so it leaves. On the off-chance the plant gets attacked by the pest anyway, the pest won’t stand a chance. The high sugar level of the plant sap ferments to alcohol in the insect’s body. As they can’t digest the alcohol the insects die. Natural resistance with no artificial and toxic chemicals used!

Every plant has different ‚ideal‘ Brix levels and many can be found online. Most important to understand is that raising a plant’s Brix is a good thing and should be the goal of any grower.

HOW TO RAISE BRIX LEVELS?

Proper mineralization – This is the key to everything. One of the main reasons why plants get sick (low Brix) is a lack of tools to create and transport good compounds. Getting more minerals (in proper form) into your plants is going to raise the Brix level and provide the tools the plant needs to produce other natural immune compounds.

Two keys to this are (mono-)silicic acid and L-amino acids (which, combined with microlife stimulation form the base of the Aptus philosophy on feeding plants.). Both of these compounds help to increase the bioavailability (absorption and transport) of minerals into and throughout the plant. The less the plant has to work to bring in food, the more it can bring in. More minerals equal higher Brix.

Calcium plays an essential role in increasing Brix levels as well. Since calcium is immobile and near the beginning of the biochemical sequence of plant nutrition, it’s absorption affects most other minerals. If calcium availability and uptake are optimized, then all other mineral uptake will be more balanced and effective.

Another thing to keep in mind is that mineral salts (from cheap chemical fertilizers) can be detrimental to mineralization. Excessive salts cause imbalance and are toxic to living tissue and cause stress that further weakens the plant. In a truly diverse organic environment where soil microlife and plants are working fully in their place, pest problems are isolated or non-existent.